13 Oct Screen International’s “films that popped at Venice and Toronto”, featuring Journey’s End.

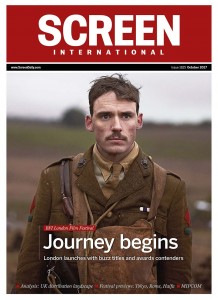

The October issue of Screen features Sam Claflin as its front cover, in character as Captain Stanhope from Journey’s End.

This follows on from previous Screen articles praising the film, with Fionnuala Halligan including Journey’s End as one of her “10 films that stood out at the Venice and Toronto film festivals”, and Allan Hunter’s fantastic review, which reads as follows:

“R.C. Sheriff’s landmark play Journey’s End was first staged in 1928 and filmed in 1930. It has been revived, revisited and remade by successive generations, which rather begs the question of whether the world needs yet another version of this old warhorse. Saul Dibb provides an emphatic answer with a robust, sinewy production that honours the film’s enduring themes and proves that it has stood the test of time.

Continuing centenary commemorations of key events in World War One should provide an ideal backdrop for a theatrical release, but it is the quality of the film itself that should strike audiences seeking thoughtful, emotionally-charged great British drama.

Dibb’s smartest moves are to trust the material and strive to render it in as cinematic a way as possible. Journey’s End was never a sweeping anti-war statement but more of an intimate portrait of men at war; the tender bonds formed between brothers in arms and the unbearable burdens of command.

Raleigh (Asa Butterfield) arrives at the front in March 1918. A state of stalemate has existed for months, but a fresh German offensive is expected. Battle-hardened veterans like Osborne (Paul Bettany) and Trotter (Stephen Graham) indulge Raleigh’s puppy dog-like enthusiasm. His presence is only resented by former schoolmate and commanding officer Stanhope (Sam Claflin); a man marinated in whisky and barely keeping things together as he prepares to lead his men to death or glory.

When Raleigh arrives at the front line, the camera’s close scrutiny seems to magnify his callow features and wide-eyed wonder at the world he enters. Sound design provides a vivid imprint of squelching mud, the fireworks whizz of gunfire and the elevated breathing of those about to die. Laurie Rose’s bobbing camerawork draws us into the reality of the moment and makes us feel the claustrophobic confines of trenches, a makeshift kitchen or a tiny shelter. There is nothing in either Dibb’s approach or Simon Reade’s screenplay that makes it feel old hat or stuffily theatrical.

Reade’s screenplay is filled with telling little human touches — the way food becomes a focal point of existence, the gallows humour, the small acts of kindness, the distracting whimsy. There’s also a very British sense of understatement in the way death is met with a stoical shrug and a hearty “cheerio, then”. In Journey’s End, war is the ultimate expression of the need to keep calm and carry on.

There isn’t a weak link in a pitch perfect ensemble cast that stretches from Paul Bettany’s kindly, honourable father figure Osborne, to Toby Jones philosophical cook Mason and Sam Claflin’s embittered leader. All underplay beautifully, conveying the quiet reality of a desperate situation. It is a governing sense of restraint that lends the film such an emotional kick, and breathes fresh life into an old classic.”

Allan Hunter

Screen Daily

https://www.screendaily.com/reviews/journeys-end-toronto-review/5122182.article